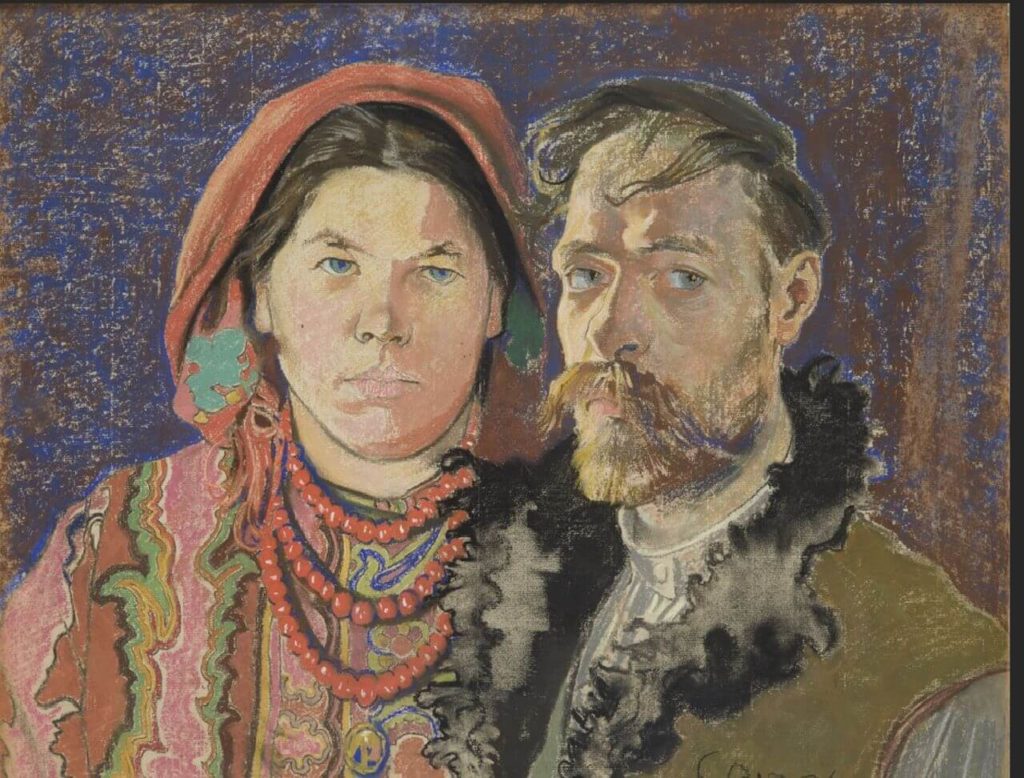

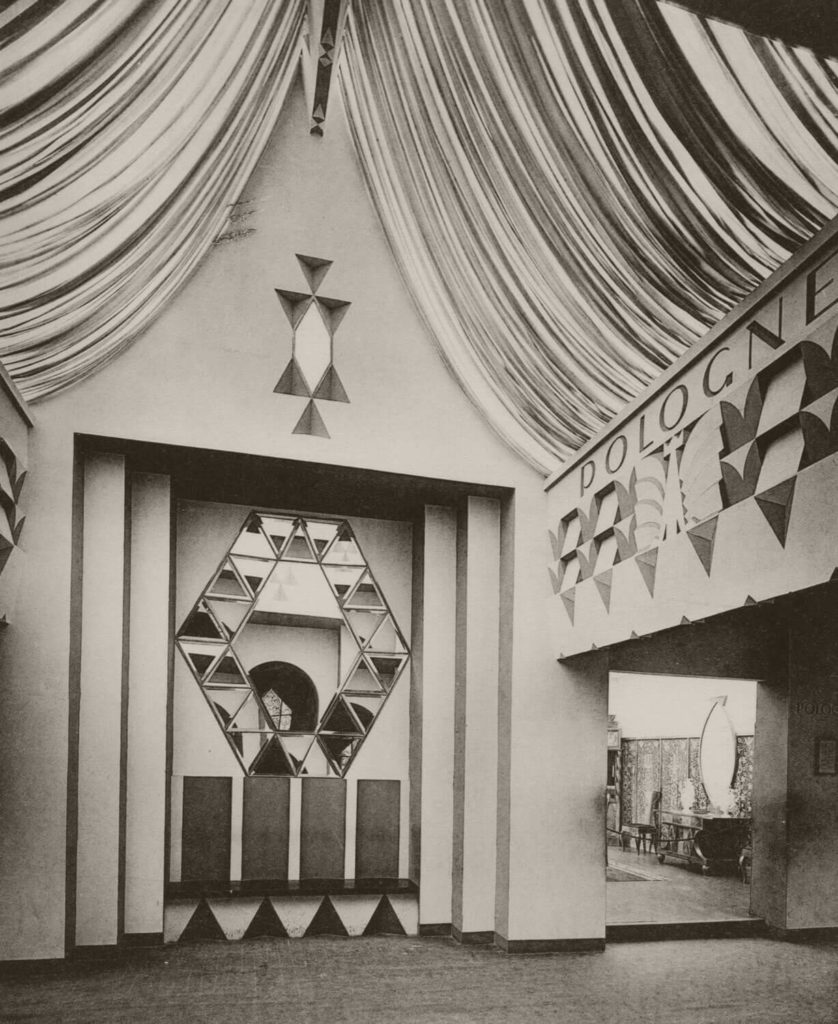

Perhaps talking about Poland as a country during the Partitions was indeed impossible, yet referring to it as a nation wouldn’t be out of the question.

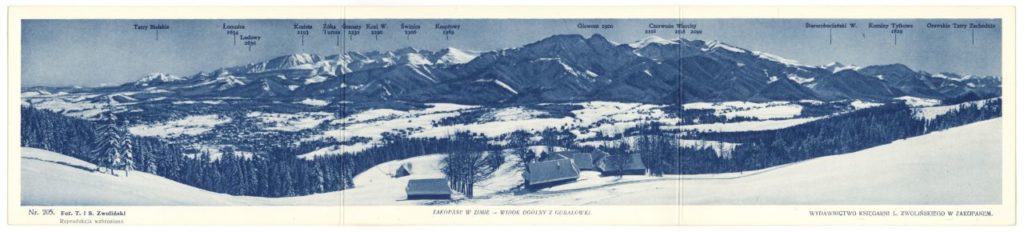

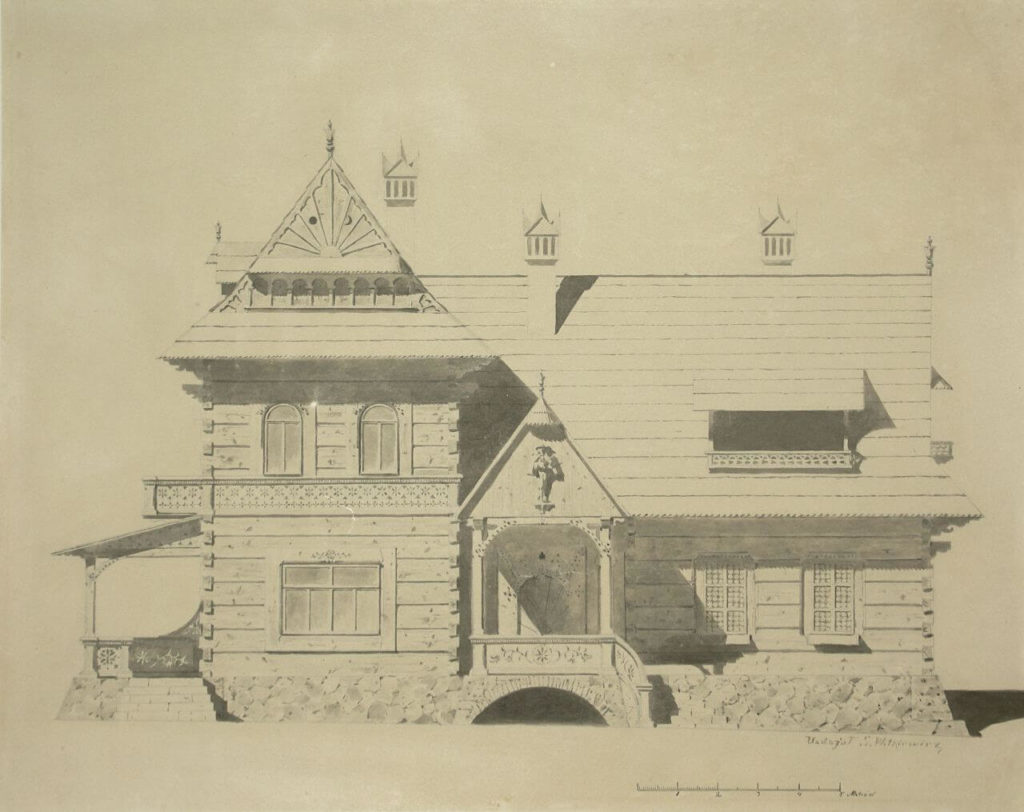

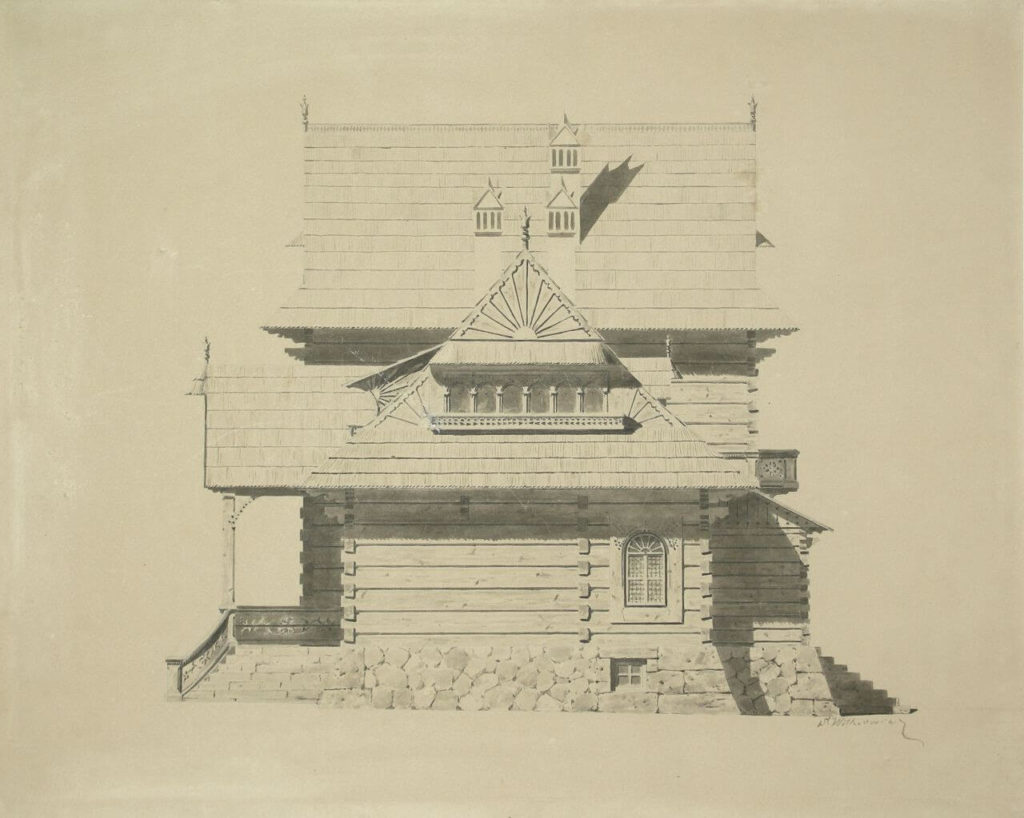

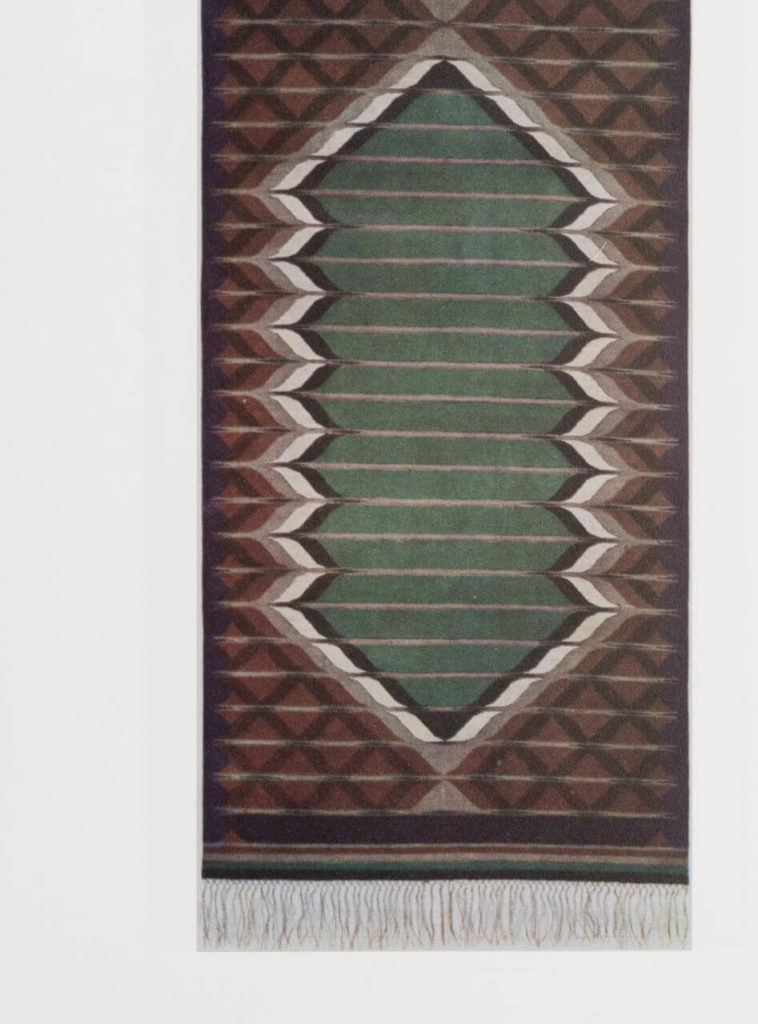

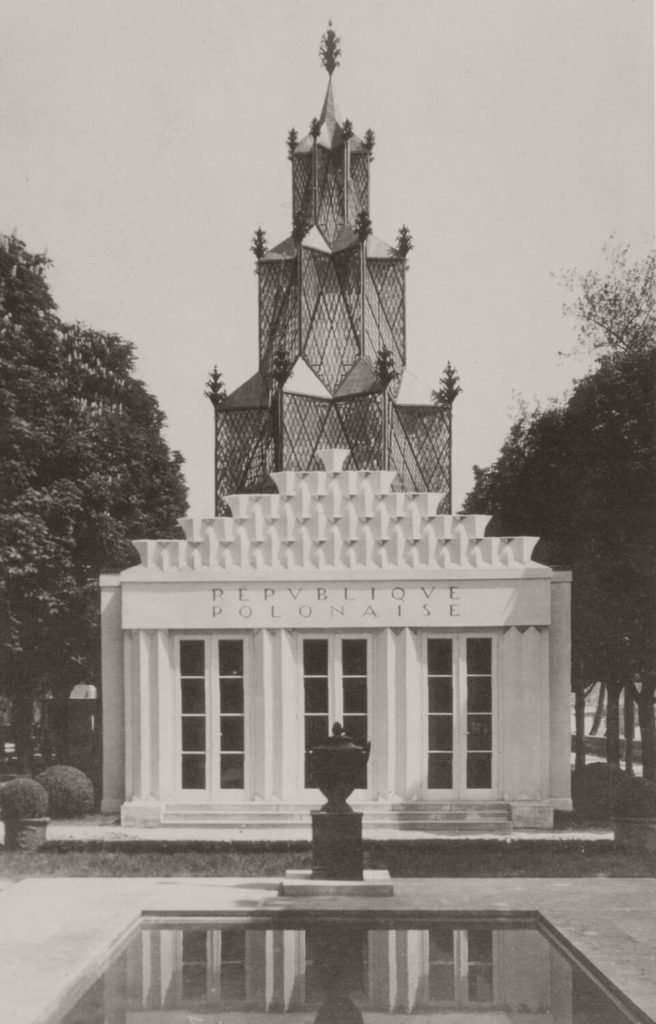

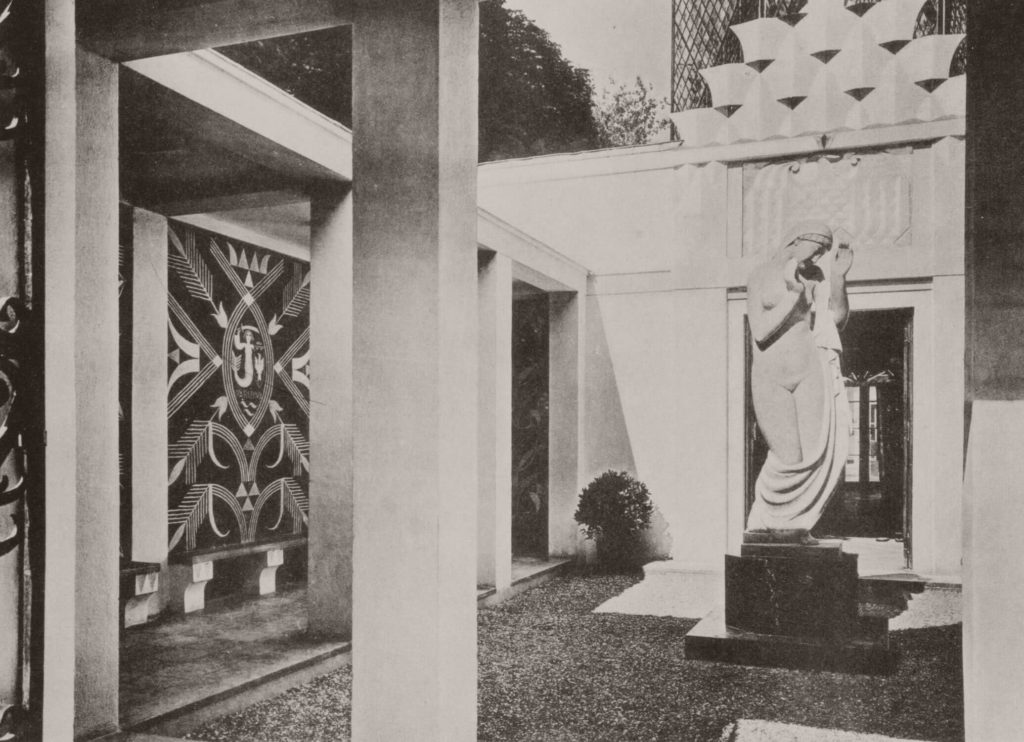

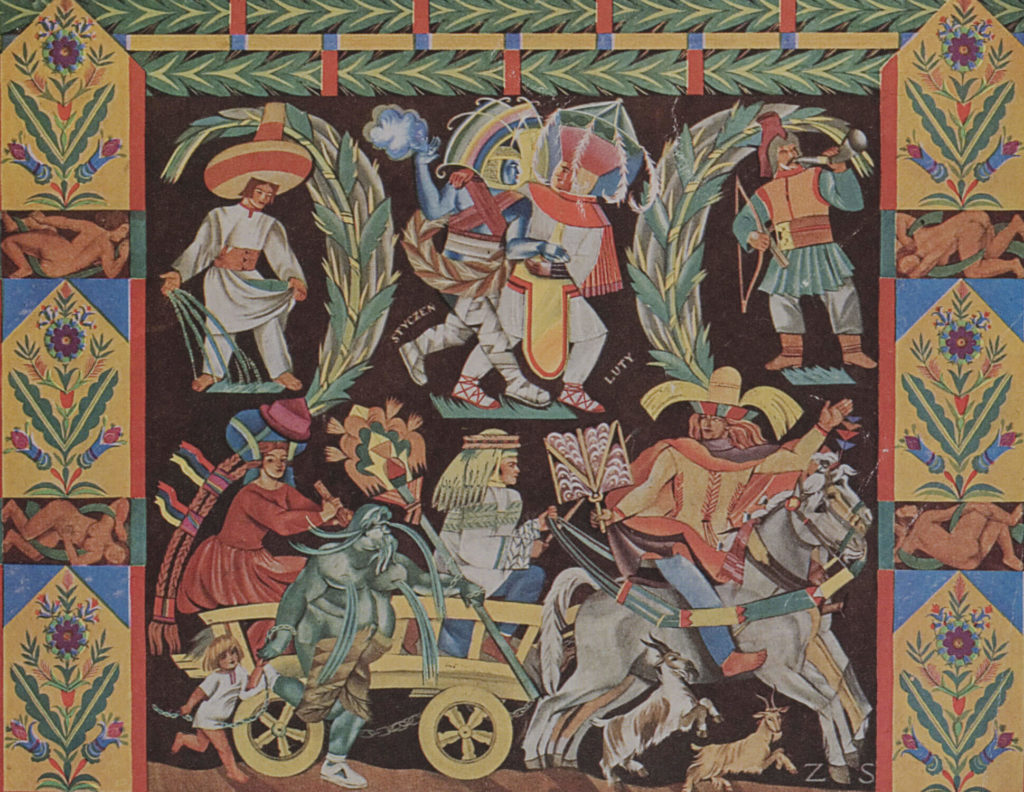

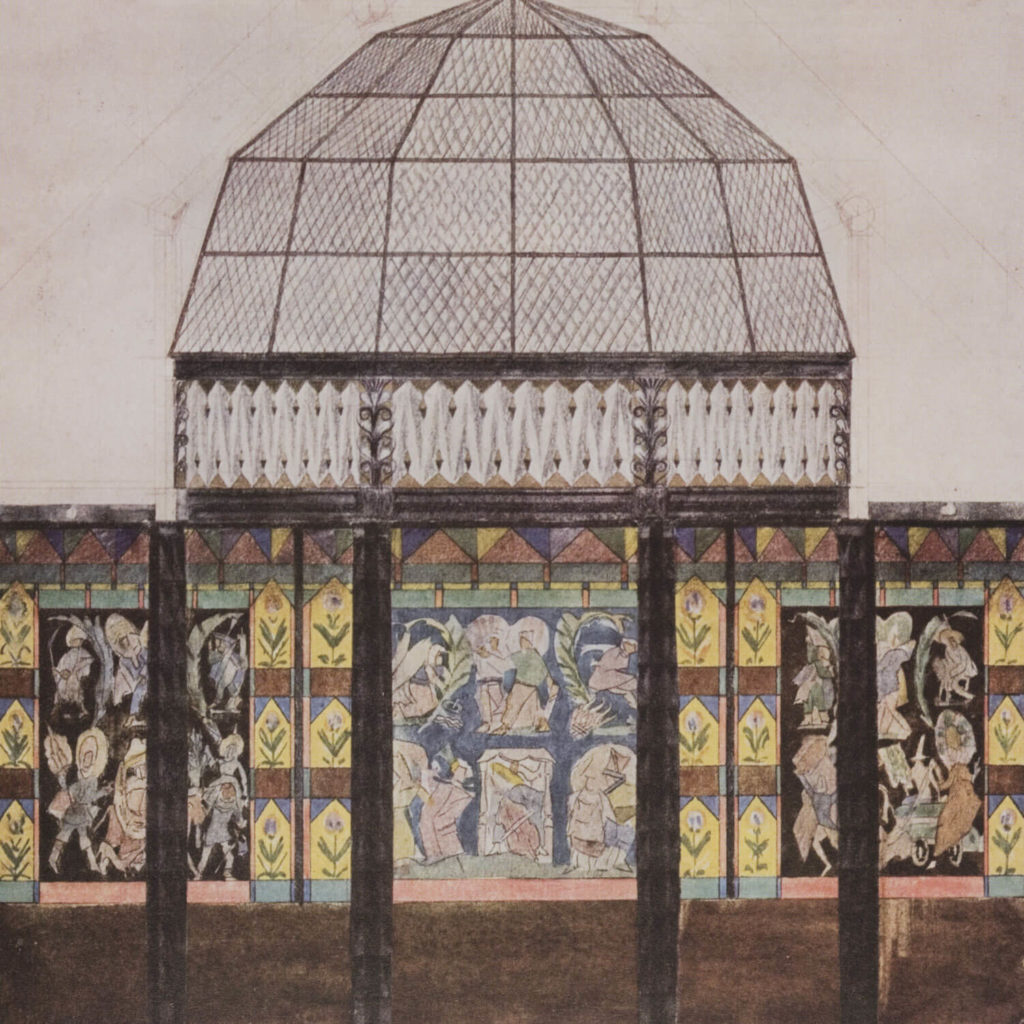

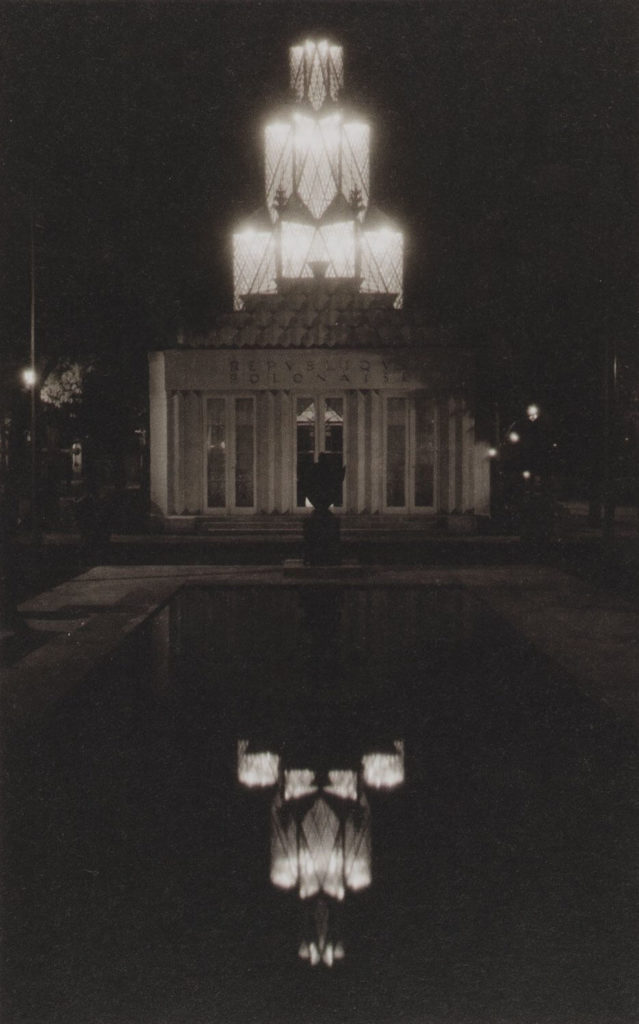

In the face of these divisions, Poles clung to culture as a safeguard against disappearance. Poles turned to their regional cultural traditions for a feeling of national identity and belonging. It was in the south, under the Austrian Partition, where Poles enjoyed the greatest social and cultural freedoms. And it is here, in Galicia at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, that certain ideas emerged which, for a long time, set the course of the development of Polish applied art and, later, that of industrial design.