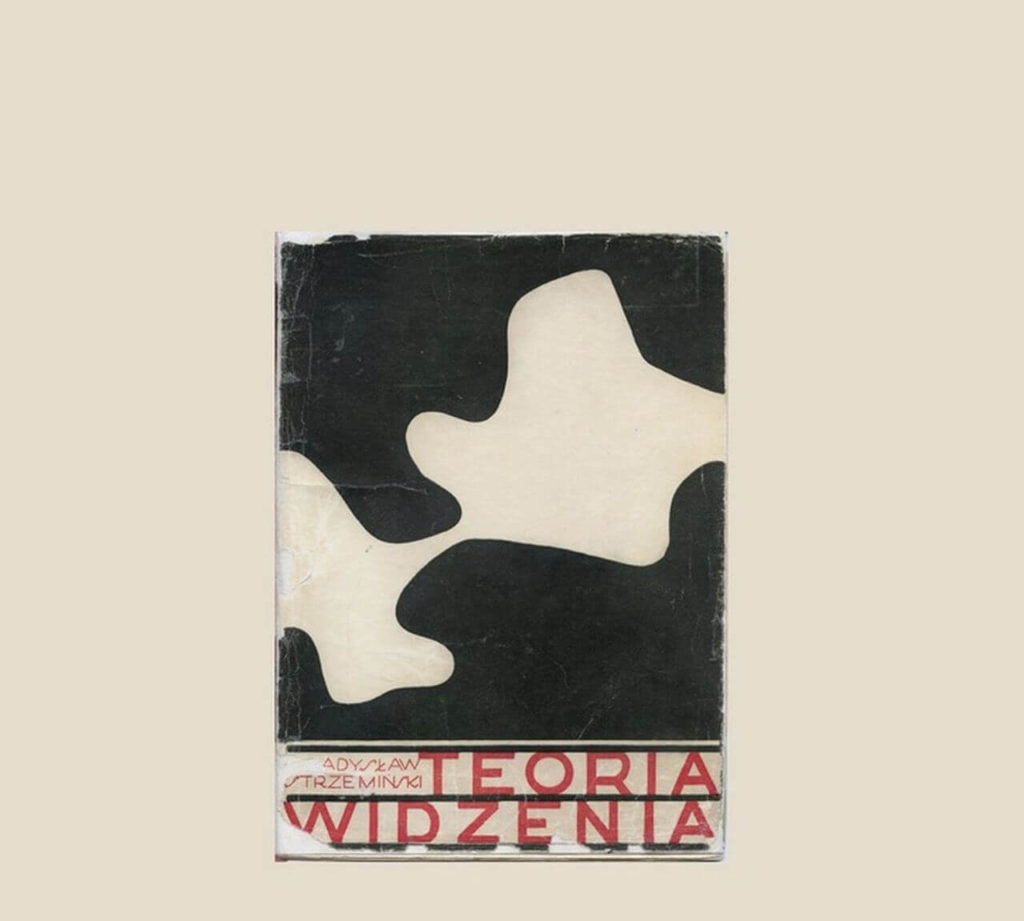

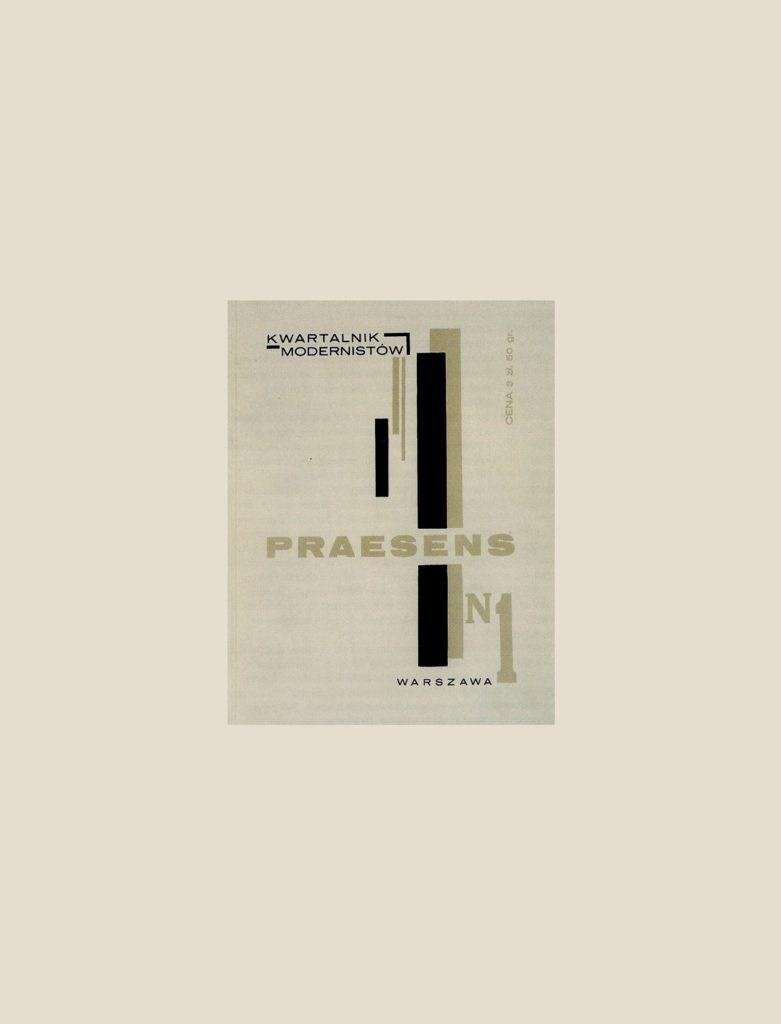

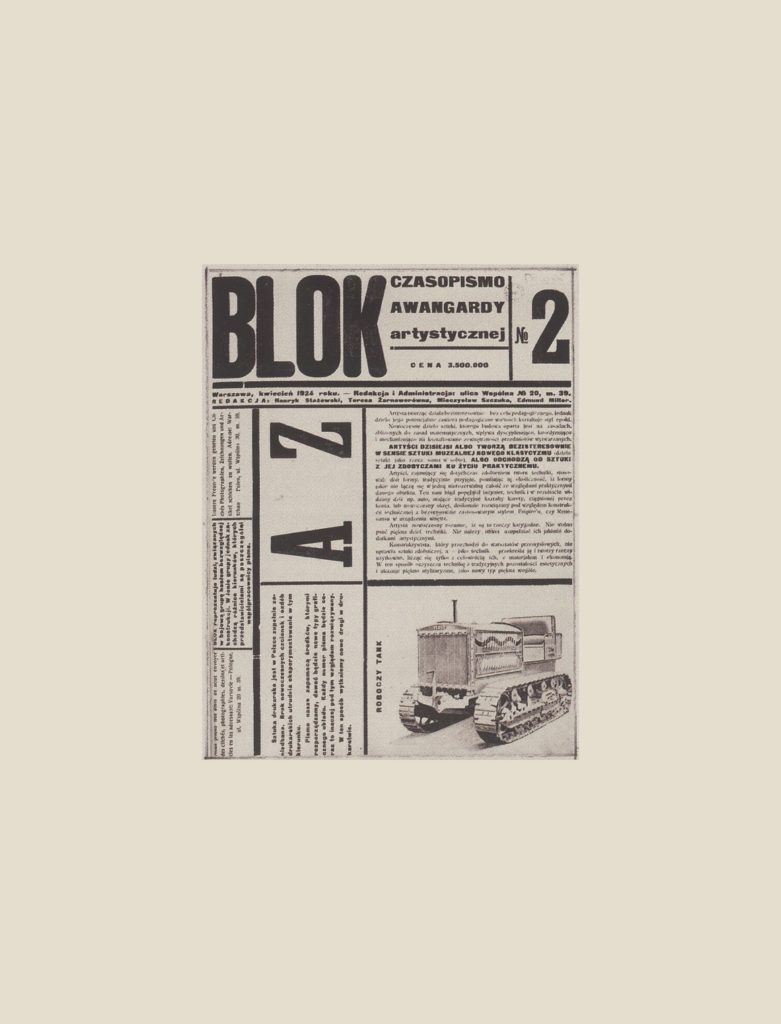

As it turns out, not everyone was delighted with Poland’s spectacular success at the World’s Fair in Paris. The Polish avant-garde community, namely members of the BLOK group (1924), thought that tapping into traditional folk art did not accurately present the newest trends in Polish art and design. In 1926 in Warsaw, two opposing design groups were formed. The Spółdzielnia Artystów ŁAD (ŁAD Artists’ Co-operative) was heir to the concepts put forward by the Kraków Workshops. The Praesens group (1926), an initiative created by architects, graduates of the Architecture Faculty of the Warsaw University of Technology and modern artists, on the other hand, wanted a clean break from traditional forms. Their interests focused on the industrialisation and standardisation of the construction and design of everyday objects.

Chapter 2 – In the Name of Avant-Garde

IN THE NAME

OF AVANT-GARDE

1920s

The interwar period is an extremely exciting time in the history of Poland. Finally an independent country, Poland has the opportunity to face its past as well as the challenges of the future. Widespread social changes go hand in hand with changes in art, architecture and culture in general. On the one hand, designers are nurturing their new found traditions, on the other, they are looking towards the future. Avant-garde artists bring with them slogans of functionalism and modern art, which begin to impact everyday life.

FORM AND FUNCTION

The Praesens group took American and European theories of modernity and tried to make them work on Polish soil. In 1928, Praesens became the Polish representative of the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (International Congresses of Modern Architecture). The concepts of functionalism found their place not only in designs for large apartment complexes, but also in private homes. Architects built themselves homes based on the same principles, i.e. the Brukalski Villa or the Lachert House. In Poland, modernity meant that form came from function.

THE BARE MINIMUM

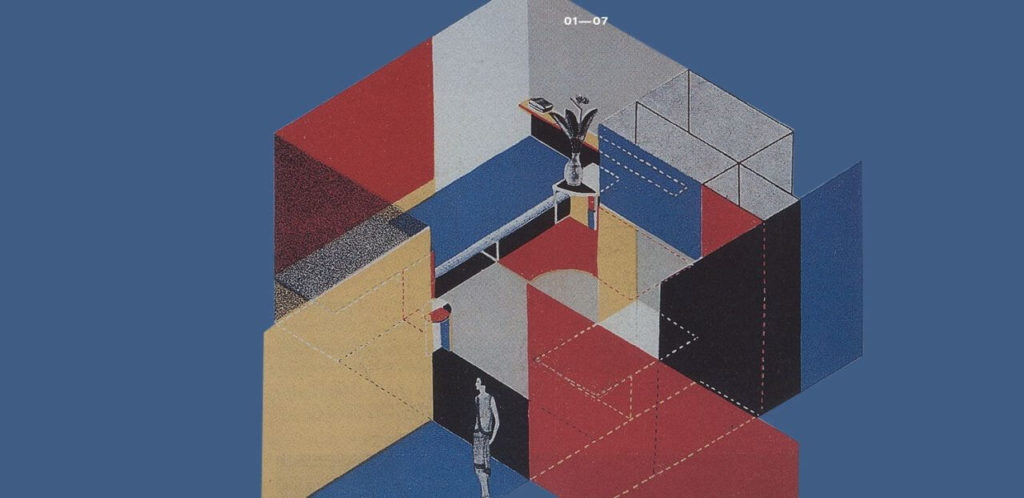

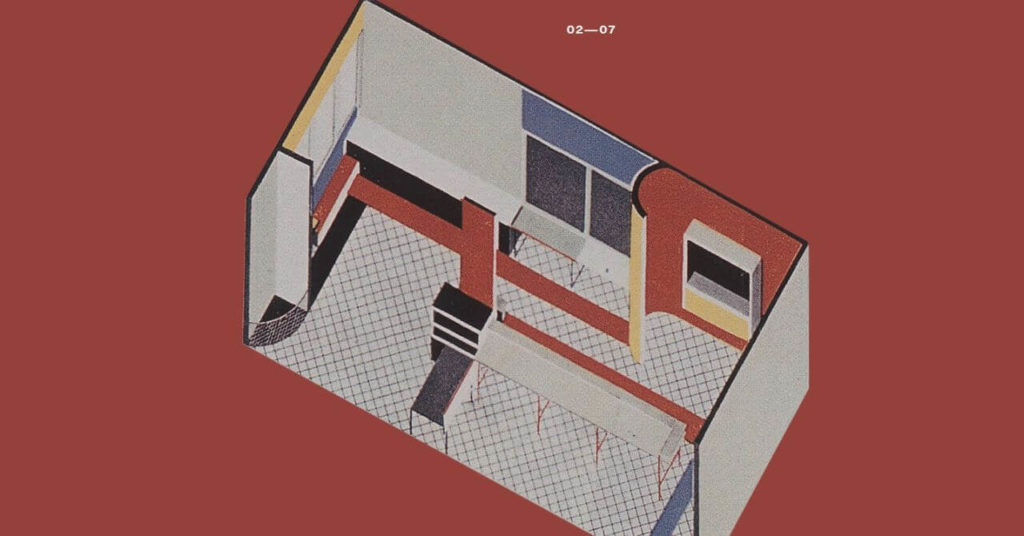

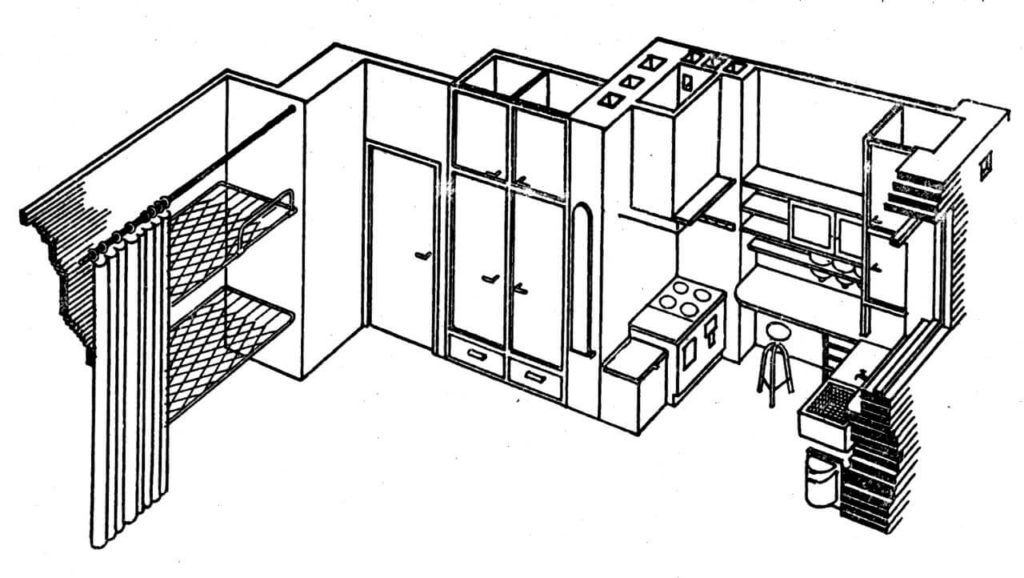

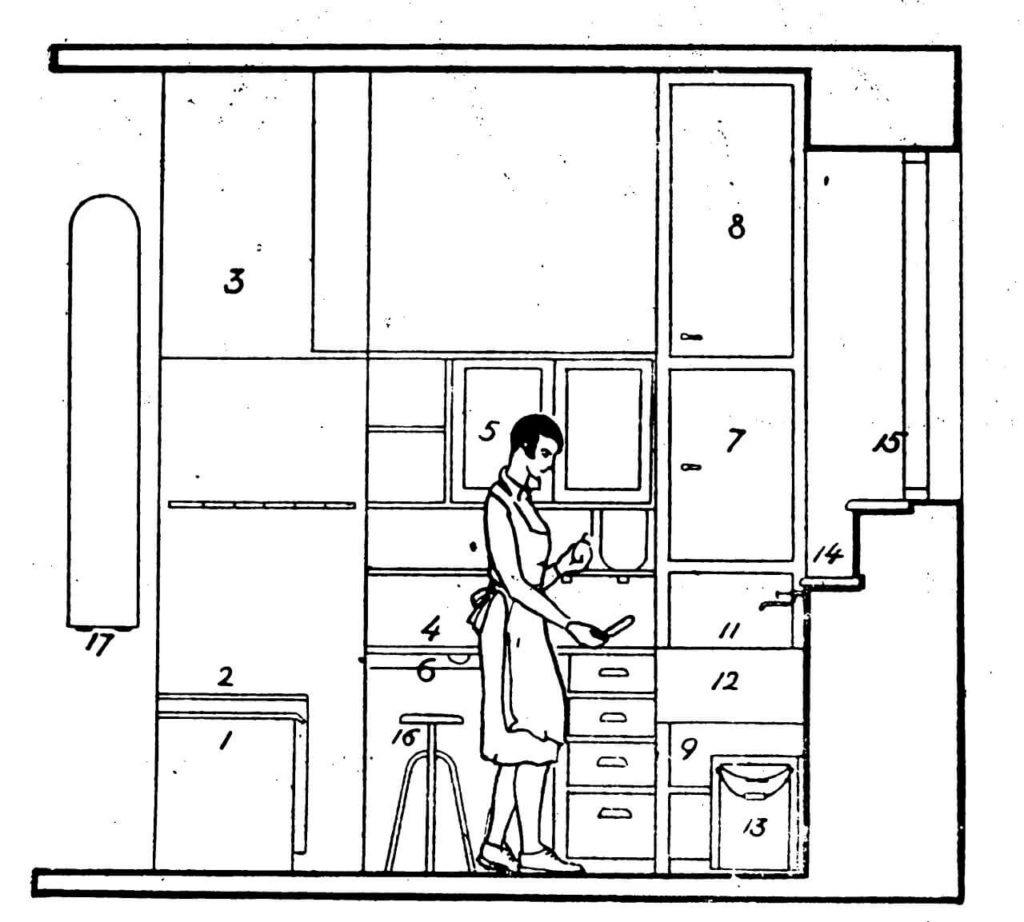

In the 1920s, designing flats for the poorest part of society took centre stage all over Europe. It was the main topic of the 2nd International Congress of Modern Architecture in Frankfurt in 1929. In 1930, Praesens presented an exhibition entitled ‘The Smallest Flat’. In four newly constructed blocks of flats, designed by the husband-and-wife duo Barbara and Stanisław Brukalski, Praesens presented as follows: distinguished designs by international and Polish architects (Building A), different types of materials (Building B) and 13 fully-furnished and equipped small flats (Buildings C & D), in which designers presented new ways of thinking about interior design such as multifunctional furniture. It was the first of many such presentations in the years to come.

MODERNISM HIGH UP

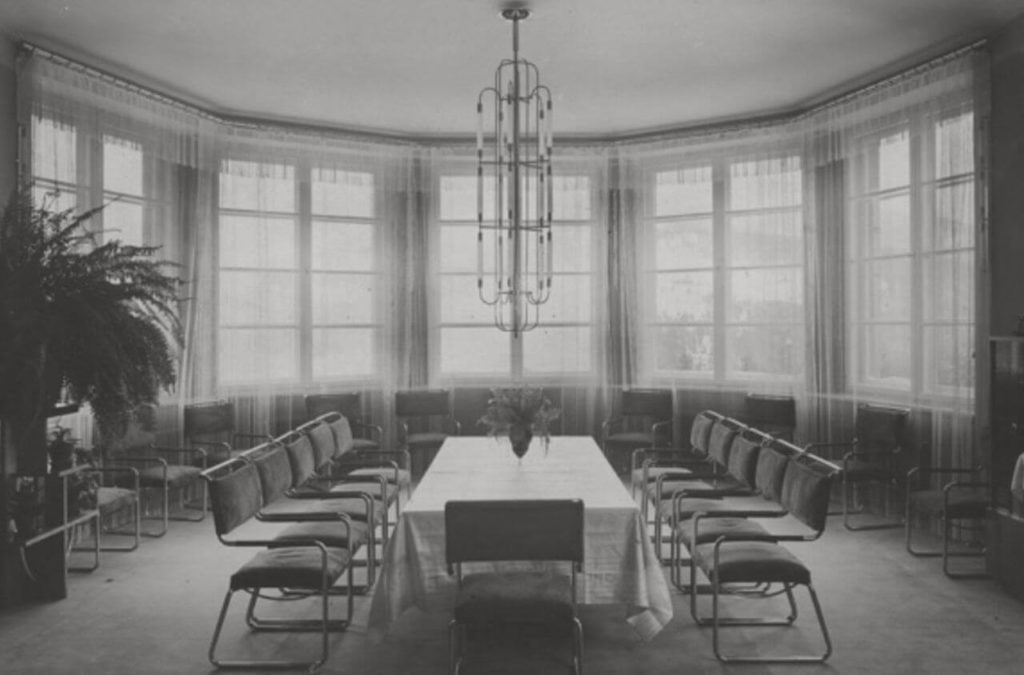

In the years 1928-1931, a new residence for the President of the Republic of Poland, Ignacy Mościcki, was built in the town of Wisła by architects Adolf Szyszko-Bohusz, Andrzej Pronaszko and Włodzimierz Padlewski. Despite the passage of almost a century from when it was built, its modern character remains invariably captivating: from the building’s simple exterior, to each detail in its interior. The use of the language of modernity in a residence for the highest position in the country was a very bold move at the time.

The design of the residence plays with geometric forms and is finished with flat roofs (high rooftops were added later), large windows which open out onto the beautiful forest landscape and let in plenty of light. Thanks to this light, the interiors are bright and seem even more spacious. The modernist furniture is made of bent steel pipes, designed by Włodzimierz Padlewski and built by Konrad Jarnuszkiewicz i S-ka, which was the main manufacturer of metal avant-garde furniture at the time.

The furniture is clearly divided into functional units. Light and modern, the quality and the choice of materials used – wood, plush, leather – emphasises the rank of the endeavour. The elegant lighting, in the style of Polish Art Deco, was designed by Edmund Bartłomiejczyk and manufactured by Antoni Marciniak’s Factory of Electric Chandeliers based in Warsaw.

The Presidential Palace in Wisła, a building designed for Poland’s highest political echelons, is a unique example of the use of the language of modernity in design and architecture. The palace shows a new approach to design – and new relationships between the designer and the manufacturer. It is a living example of the shift from applied arts to functional design in Poland, a design gem which we can admire to this day.