“We want to be modern (…) the time has come to liquidate the extensive inventories of contemporary technical and artistic thought.“

—Jerzy Hryniewiecki, 1956

Chapter 4 – Behind the curtain

BEHIND

THE CURTAIN

1940 –1950s

World War II took an immeasurable toll on Poland. The country suffered enormous loss. The war curbed the development of many fields, design included. Rising from the ashes was not going to be an easy task – especially under the communist regime and its love of socialist realism. The Polish artistic community was quick to try and move past the ruins of war. Pre-war fine arts academies were quickly re-opened and even some new art schools were established. Design was present at all of them, as was the new term: ‘industrial design’.

The 1950s is, yet again, a time of political upheaval. The Khrushchev Thaw, which came after Stalin’s death, brought a softening of the social realist norms in art and design dictated by the communist regime. All of a sudden, artists and designers have more freedom to experiment, to explore new techniques, new styles, new materials. The Iron Curtain isn’t as impenetrable as it once was – the government wants to show the world what Poland has to offer. Many designs finally make it into production. And even make it to store shelves.

FOLK IS BACK

DON QUIXOTE IN A SKIRT

Wanda Telakowska was the person behind the concept of ‘beauty everyday and for everyone’ and the first post-war state institution created to help artists work with industry. In 1945, Telakowska stood at the helm of the Planning Division at the Ministry of Culture and the Arts. In 1947, a separate department was formed: the Aesthetic Production Supervision Bureau (Biuro Nadzoru Estetyki Produkcji). It was here that the phrase ‘industrial design’ was first used in Poland.

1950 saw the creation of the Institute of Industrial Design (Instytut Wzornictwa Przemysłowego, or IWP). The institute conducted research and organised lectures, seminars and panel discussions, as well as designated councils to review designs for serial production. Telakowska, the founding director of the institute, was known as the ‘national Joanne of Arc of design’. One of the employees of IWP once described her – and her tireless work to promote design in Poland – as ‘Don Quixote in a skirt’.

FOLK ART FOR CITY FOLK

Folk art, which was always a source of inspiration for Polish designers, found its way back onto their radar screens after World War II. Starting in 1949, socialist realism was a clear blueprint for artists – they couldn’t stray very far from the communist ‘norms’. At a time when modernity was taboo, as were many historical motifs, artists looked once again to Poland’s folk traditions. In 1949, the Headquarters of the Folk and Artistic Industry (Centrala Przemysłu Ludowego i Artystycznego, or CPLiA) was established, under the leadership of another dame of Polish design, Zofia Szydłowska, to supervise the work of folk artists and ensure their crafts made it to store shelves around the country – they were creating folk art for city folk.

At the same time, the Institute of Industrial Design under Wanda Telakowska was hard at work. She saw folk art not only as a style, but rather as a source of inspiration for designers all over Poland. She would send groups of designers to centres of Polish folk art, such as Podhale, Zalipie and Kurpiów, to learn the traditional patterns and techniques they used. With this newfound knowledge, the designers would return to Warsaw to create new designs based on these traditional patterns that would be created for mass production, and thus, a wider audience. This model of co-operation proved particular effective when it came to fabric and ceramic design.

NEW LOOK

FINE PRINT

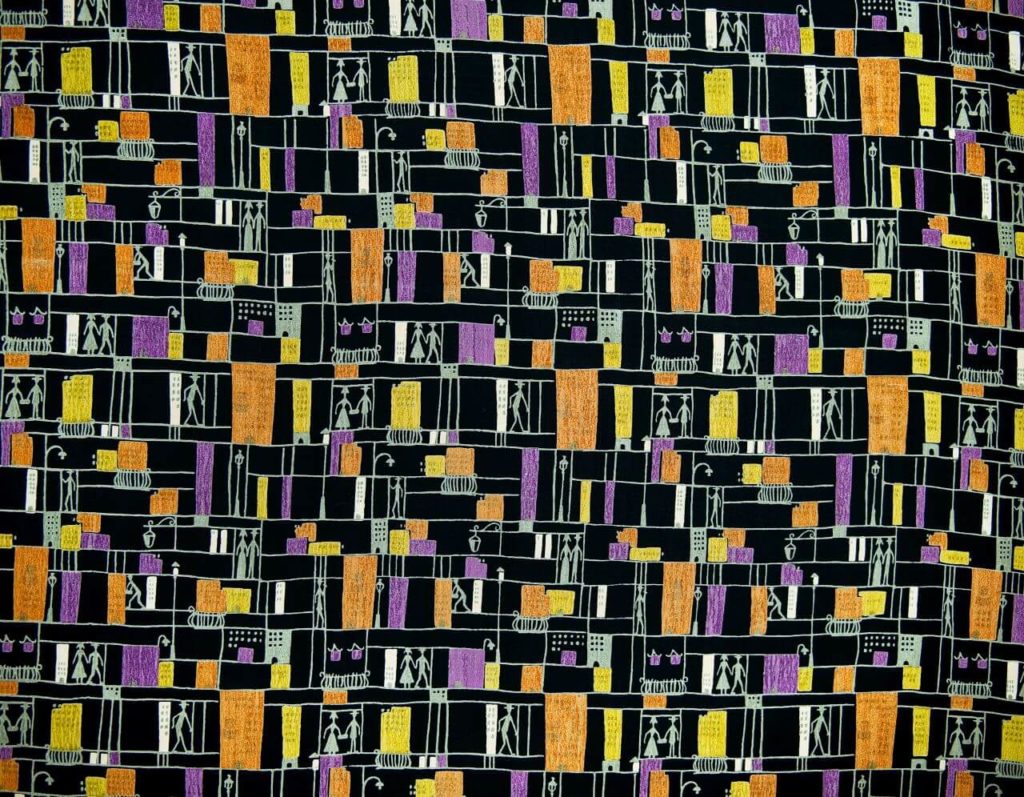

The New Look took over cafes, living rooms and… closets. The end of the 1950s saw an explosion of vibrant, colourful fabrics – printed and painted. Simple lines, repetitive patterns, interesting textures, black and white contrasted with bursts of colour. These fabrics made their way into living rooms and onto runways.

“Too grey is the external image of our everyday society. Modern technology shares generously – the richness and intensity of colour, strong light, wide space, the lightness of the material.“

—Jerzy Hryniewiecki, Projekt magazine, 1956

The prints and patterns created by Alicja Wyszogrodzka are the perfect example of the vibrancy and variety of fabrics created at the time. One of her most recognisable patterns has to be Panny (Ladies): women in flared dresses seemingly dance along the edge of the fabric. With their black and white silhouettes up against a bright colourful background, they look as if they are strutting on a catwalk. Their energy is palpable. Wyszogrodzka’s fabrics were very versatile. In her MDM (1955) fabric, she used simple lines to create a complicated and rich pattern that showed modern city life. Her kerchief with a “quilted” motif of a stylised female head on a red-and-amaranthine background, with a graphic design or composition in red-and-gold, more resembles a poster than an applied fabric. Meanwhile, Fish was an interpretation of geometrical patterns for the Beach series.

BEYOND SCULPTURE

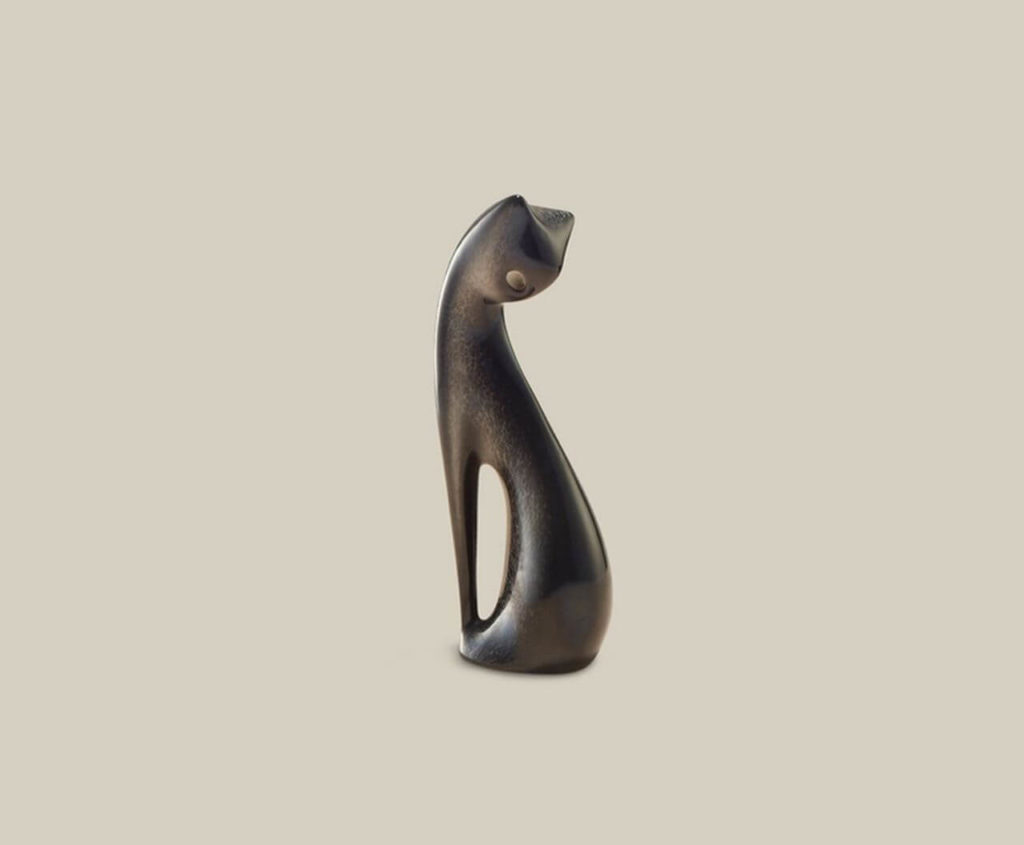

With the Thaw, a new global trend in design came to Poland: organic design. It meant flowing, natural forms, undulating lines, dynamic curves and powerful arches. Sculpture came to the fore. And it is sculptors who created a brand new phenomenon in Polish design – the bibelot, or trinket.

Henryk Jędrasiak, Mieczysław Naruszewicz, Lubomir Tomaszewski and Hanna Orthwein began making human and animal figurines – their streamlined silhouettes seemed as if caught mid-movement. They were being produced in the biggest porcelain factories and became extremely popular.

In the style known as New Look, the figurines were a must-have for any stylish home and were the highlight of fairs and exhibitions around the globe – in New York, Chicago, Moscow and Berlin. The British magazine The Studio even presented them in their annual best design edition in 1959.

TAKE A SEAT

MUSZELKA CHAIR

The opportunity to explore led Polish designers to start experimenting with plywood and wicker. Wicker had of course been used for centuries, however plywood was a relatively new material and hadn’t really been used for manufacturing furniture in Poland. The flexibility and endurance of plywood gave designers free rein for experimenting with construction. The artistic possibilities of plywood were first explored by Jan Kurzątkowski, a designer from the ŁAD Artists’ Co-operative and teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. His disciples continued his work. Jan Krzątkowski’s student Teresa Kruszewska debuted with a set of furniture for the home.

It included the iconic Muszelka (Shell) chair. Shaped like a shell, the seat itself was made of plywood and sat on a sturdy steel frame. Then, Kruszewska wound colourful plastic string around the frame and seat over and over and over, creating a ‘woven’ chair. It came in a variety of colours and people absolutely loved it! Woven stools, baskets and even knock-off Muszelka chairs soon followed. The Muszelka chair stood out in 1956 and quickly became an icon of Polish design. Even though it was admired and presented at numerous trade shows around the globe, it was never actually put into mass production.

PŁUCKA CHAIR

Maria Chomentowska, another one of Krzątkowski’s students, also used plywood in her designs. In search of a comfortable seat, the designer tried to take full advantage of plywood’s flexibility. The Płucka (Little Lungs) chair’s backrest consisted of two parts which, in shape, resembled… little lungs. Connected by a small leather strap, they gave the material some give and the user could lean back comfortably. The seat itself was also an interesting shape – its distinctive incisions allowed for the backrest to be hooked into the seat and almost seamlessly join the legs. The Płucka chair was both extremely simple and extraordinarily decorative. A wise and wonderful use of plywood.

“I would like to remind you that modern furniture should not be a capital investment: solid, expensive, bought to last a lifetime. It should be painless for its owner’s pocket and change with the needs of the household.”

— Maria Chomentowska

A587

The A587 chair designed by Marian Sigmund, one of the founders of the ŁAD Artists’ Co-operative, was intended for export to Great Britain to be used as a school seat. The bentwood structure, both from plywood and solid beech wood, as well as the contrast between natural and black-dyed wood made the chair unique in its simplicity and beauty. Pupils today would be lucky to spend their school days in such a classy chair! Originally designed in 1957, the A587 chair was produced in 1958 at the Bentwood Furniture Factory in Jasienica. The factory, today the well-known Polish furniture company PAGED, came out with a new edition of the chair for its 100th anniversary in 2017.

CHULIGAN CHAIR

Władysław Wołkowski was known as the ‘Michelangelo of Wicker’. A fascination with nature lay at the core of Wołkowski’s aesthetic and philosophical concepts. Wołkowski weaved, braided and pulled, looking for harmony in asymmetry. He never used existing designs. His Chuligan (Hooligan) chair is precisely that – a hooligan. Completely out of whack, not in keeping with standard expectations and kind of cheeky, one can’t help but be mesmerised by it. It is living proof that even something as simple as a wicker chair can be surprising.

“I can’t stand the monotony of technological civilisation, of industrial production standards. In nature there is infinite diversity and great harmony. There are no two leaves that are the same on a tree, and yet there are thousands of them on the tree.”

— Władysław Wołkowski

Acquiring plastics behind the Iron Curtain was not easy. Despite these difficulties, a few Polish designers managed to obtain them and began experimenting. Furniture with elements made from materials such as igelit, a popular polyvinyl chloride at the time, began to pop up in cafés and at exhibitions in big cities. More and more often, Poles were asking where and when they would be able to buy these chairs and tables for themselves. The biggest show of plastic furniture took place in 1958 in Kraków. It was the first time that people could not only admire it, but also buy it. They could take pieces created by Jan Szczurek, Halina Cieślicka, Maria Michajłow and Witold Popławski, straight home to their living and dining rooms. Resin was even harder to get your hands on. But there were always exceptions! And this exception lead to the creation of one of Poland’s most iconic designs.

ARMCHAIR

The Armchair was ahead of its time. And people loved it. The chair was so popular it was featured in a number of Polish movies and a French furniture manufacturer was even interested in producing it. Modzelewski obtained a patent but was banned from selling it to the French by the communist regime. And so, in the following decades, the chair was only made-to-order. This instant icon had to wait half a century to finally go into mass production. Modzelewski’s iconic design remains fresh and compelling to this day. The Polish company VZÓR took it upon themselves to bring the armchair to today’s consumers. In 1958, despite plastics and resins being so inaccessible and Polish designers being relatively uninterested in the technology used for mass production, the artist and designer Roman Modzelewski created a surprising armchair. What’s so special about it? Well, it was one of the earliest Polish examples of polyester-glass laminate furniture. And that’s not all. Its fully-closed organic form was like nothing else created at the time – it impressed even Le Corbusier himself! Modzelewski created an armchair that was both beautiful and comfortable, and managed to avoid the imperfections of the material.

ON THE ROAD

SYRENA SPORT

Modernity took over more than Polish households – modernity was taking to the roads. Cars and scooters were also a fashion, or rather design, statement! As Poland’s first post-war car, the SYRENA was created to be a popular car – and it quickly lived up to its potential. Designed by the FSO (Fabryka Samochodów Osobowych, in English: Passenger Automobile Factory) under the supervision of Stanisław Panczakiewicz, it significantly changed Poland’s roads.

The SYRENA SPORT from 1960 was designed by Cezary Nawrot who wanted to create the ‘car of his dreams’: red, sleek with a modern, sophisticated body modelled from laminate. Poles were ready for a classy car for two, but, yet again, the Polish People’s Republic believed that it was ‘too extravagant’. This dream car never hit the open road. At the end of the 1970s, the ‘the most beautiful car behind the Iron Curtain’ was officially destroyed. The red convertible was to remain, like true mermaids, the stuff of legends.

OSA: THE POLISH VESPA

The famous Italian Vespa was first introduced in 1946 by Piaggio. Everyone longed to hop on a Vespa and ride around without a care in the world! And so, Poland needed it’s own ‘wasp’. The Polish Osa, designed by Krzysztof Brun, Jerzy Jankowski, Tadeusz Mathia and Krzysztof Meisner, was slightly bigger and a bit sturdier than its Italian cousin. By the mid-1960s, the Warsaw Motorcycle Factory had already produced several thousand of the scooters. Its 14-inch wheels and solid suspension meant that the Osa did well not only on Poland’s uneven roads but also in rallies in Italy and Great Britain. The Osa became extremely popular – it was everywhere: on the roads, in the press and even in movies. It became synonym for youth and social change.

SMYK: THE LITTLE WONDER

Although at the time, parking may not have been a problem, Poland dreamed of a micro-car. An affordable, compact car for one and all. The SMYK car wasn’t Poland’s first attempt at a micro-car, it was, however, the most intriguing one. What made it so special? Produced in 1957 by the Design Office of the Automotive Industry, with a body designed by Janusz Zygadlewicz, the SMYK had no side doors – they were removed to make the lightweight body more solid. So how were you supposed to get in the car? The door was at the front of the car, which meant you had to open the ‘hood’ to get in. The car could fit two adults in the front and two kids (or one more adult) in the back seat. It had no trunk. Despite its ingenuity, people didn’t exactly fall in love with it – only about 20 of them were produced. Today, the SMYK can be seen at the Museums of Technology in Warsaw and Szczecin, as well as in private collections.

TAKING ON TECHNOLOGY

ALFA CAMERA

With its colourful exterior and rounded edges, the Alfa Camera, designed by Krzysztof Meisner and Olgierd Rutkowski, looked more like a toy than an actual camera. Made out of plastic and aluminium and available in a number of bright colours, the Alfa was made with young photography lovers in mind. It was easy to use and handy, but there was one peculiar feature.

Or at least it was quite unusual at the time. The Alfa’s buttons and control panels were positioned in such a way that people were forced to take vertical photos. Although today, with smartphones, this seems absolutely normal, in 1961 it was a truly big change. Despite this unusual set up, people loved the camera. Soon Alfa 2 came out and was also a bestseller.

AKAT-1

AKAT-1 was the world’s first transistor differential equation analyser. Meaning…? In short, this analogue computer, created by Polish engineer Jacek Karpiński in 1959, was a device that could solve relatively complex differential equations in real time. Karpiński’s invention was actually one of the very first personal computers ever made! In 1960, Karpiński won a UNESCO competition for the most promising young talents in the field of electronics. This opened up many opportunities for Karpiński and he chose to study at Harvard. When he was still a student, he was offered a job at IBM, but he turned them down – he wanted to return to Poland.

The incredible feat of modern technology that was the AKAT-1 needed suitable ‘packaging’. Stanisław Miedza-Tomaszewski, Andrzej Jan Wróblewski, Stanisław Siemek and Olgierd Rutkowski created a computer that looked like something straight out of a futuristic movie: a table with a built-in control panel and monitor covered in a streamlined plastic casing on splayed metal legs. The AKAT-1 was not his only groundbreaking invention. In the revolutionary 1971 K-202 mini-computer, he took all the computing power that once needed to be housed in two closets and put it into the equivalent of a shoebox. IBM’s personal computer wasn’t introduced until 1981, while Karpiński’s computers were ready to go over a decade earlier…